WHAT'S THE MATTER WITH HISTORIC PRESERVATION?

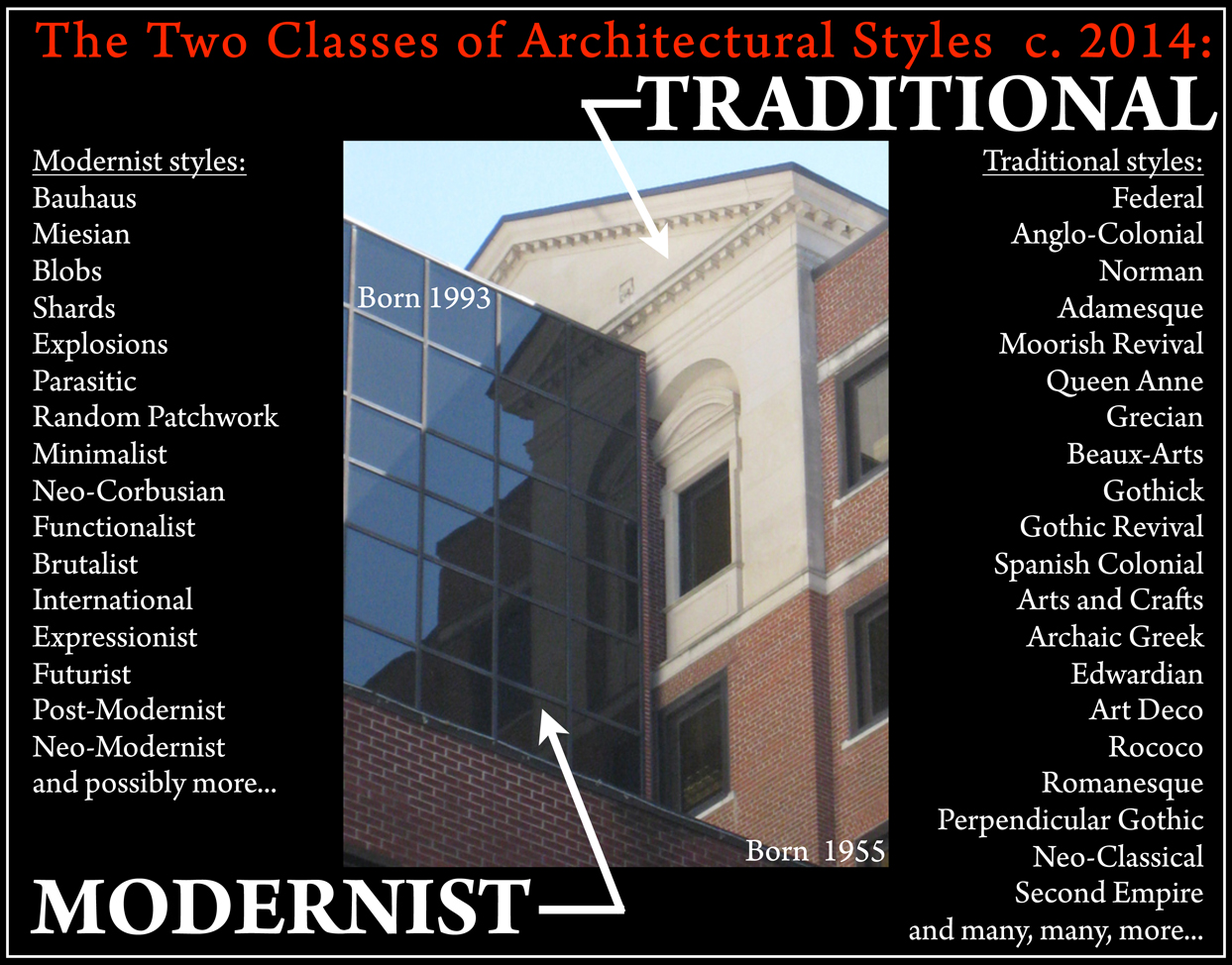

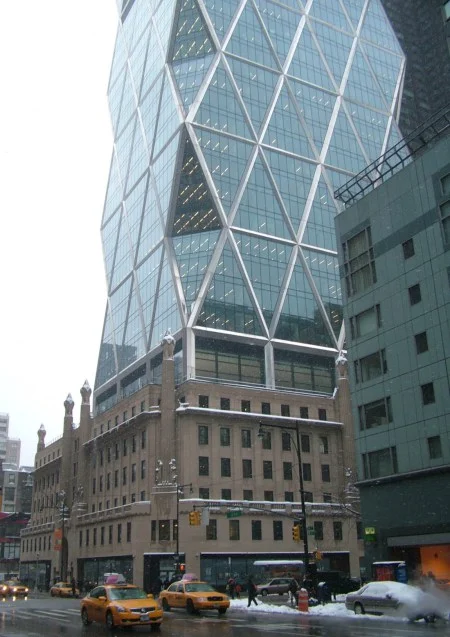

Contemporary preservation ideology condones additions such as this one in the name of "authenticity," arguing that additions and new buildings in Historic Districts must be clearly distinguishable from older ones. Unlike the early preservationists who promoted harmony in Historic Districts, today's preservationists promote contrast.

The rise of the Preservation Movement directly mirrors the rise of Modernism in architecture, and for a reason. As one of the preservationists who helped pioneer the country’s first Historic District, Samuel Gaillard Stoney, wrote: "With plenty of other urban areas available for the free exercise of individual taste, the integrity of these historic areas is preserved as an asset for the whole community.” It was because of the rise of popularity amongst architects of anti-traditional (later called "Modernist") styles - styles that result from the philosophical rejection of traditional architectural elements, motifs, and styles on principle - that the grassroots pioneering preservationists wrote Preservation Ordinances in the first place. When the early Modernist architects called for an end to traditional architecture and threatened the harmony of our cities, it was grassroots Preservationists who cordoned off areas to preserve as havens from anti-traditional - or what is today commonly called "Modernist," "modern," or (confusingly) "contemporary" - architecture. These districts were called Historic Districts not because of the history that happened there but because Modernists architects were calling for "anti-historic" architecture. Charleston, South Carolina’s 1931 Zoning Ordinance - the first in the country and the model for subsequent ordinances elsewhere - calls explicitly for "continued construction in the historic styles" (or what today are called the traditional styles) because at the time it was written, there was an alternative to doing so.

"I think the deep, dark, unspoken motivation for much of the preservation movement is not so much love of what is being preserved, as fear of what will replace it. Nobody likes to admit it, but that’s what a lot of it has been about. And I’m not sure I could blame people, at least in the nineteen-sixties and seventies, as the Landmarks Commission was being established, for thinking that way. After all, modern architecture had not exactly saved the day. It seemed to give us bigger and bigger buildings, more and more awful. It had created a few wonderful monuments, but it was a fiasco so far as urbanism was concerned. Its achievements were in the realm of individual, stand-alone, beautiful buildings, but not viable streets or neighborhoods. You would have to be crazy to think that Third Avenue was pleasanter than Park Avenue, or Madison Avenue. No wonder people feared the new forty years ago, architects were giving them every reason to."

- Paul Goldberger, 2005.

Modernist architect Le Corbusier's 1922 proposal to destroy 2 square miles in the center of Paris and replace them with high-rise apartment towers fronted with parking lots and connected by highways.

Modernists in their own words:

“The goal of a new architecture: the apostles of glass worlds, the seekers for new forms of material and construction. Naturally, this era will not be brought into being by social classes in the grip of tradition.”

- Mendelsohn, 1919

"A great epoch has begun. There exists a new spirit. Architecture is stifled by custom. The 'styles' are a lie."

- Le Corbusier, 1920

“It is essential today for architects to influence public opinions by informing the public of the fundamentals of the new architecture.”

- CIAM, 1928

“The Americans, however, are the people who, having done most for progress, remain for the most part timidly chained to dead traditions.”

- Le Corbusier, 1929

“The practice of using styles of the past on aesthetic pretexts for new structures erected in historic areas has harmful consequences. Neither the continuation of such practices nor the introduction of such initiatives will be tolerated in any form.”

- Athens Charter, 1933

"The battle for modern architecture has long been won. First, a generation of architects trained in schools that no longer teach the traditional styles has now begun to practice. Second, architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe have recently been finding commissions worthy of their talents. Third, government and industry - most notably America's giant corporations - have now become patrons of modern architecture."

- Philip Johnson, 1953

CONTEMPORARY PRESERVATION PRACTICES

Today, the Preservation movement - formerly a grassroots effort led by local community members, now a professional and academic endeavor - has itself fallen victim to Modernist philosophies, just as the architecture profession has. So even though Preservation began as a way to conserve local architectural traditions, today professional preservationists around the world are advocating against architecture that is in keeping with the local traditions of place and are supporting purposefully jarring, anti-traditional architecture instead. They are doing this not in small rogue groups but as part of the institutional establishment supported by the architectural education system and skewed interpretations of the federal preservation documents that grant tax-credits for rehabilitation. As a result, the original purpose for Historic Districts is being lost, and the local character of many historic districts is quickly diminishing. Ironically, if the current Modernist Preservation practices continue, it will be Preservation itself that leads to the slow decay and eventual loss of our built heritage.

Understand this is no indictment of the Preservation Movement. On the contrary, we are grateful for the the work of the early preservationists, and the Vision for Civic Conservation sees Preservation - the long-term maintenance of a community’s building stock - as an integral component to an overall strategy of Civic Conservation. The VCC merely seeks to have Preservation return to its original goals - along with incorporating all the lessons learned from the century-long experiment with anti-traditionalism - by adopting these new Standards for Civic Conservation. By doing so, Preservation will be taking its natural place alongside the many other important and interrelated movements to revive and maintain traditional knowledge, skills, and technology. Instead of continuing to experiment with whether Modernism can be made to fit in harmoniously with traditional urban settings, Historic Districts - and their preservationist protectors - should be leading the way on A) how to repair the damage done to Historic Districts by Modernist urban planning; B) on how to teach and encourage architects to design buildings that fit in with existing traditional buildings; and C) on how to support the revival of the traditional building arts and all the varied jobs that come with them. By doing so, Preservation will be helping restore local economies, bringing dignity back to the trades, and conserving those arts without which we can neither maintain traditional buildings nor make new ones worthy of preserving.

Preservation should:

- help repair the damage to Historic Districts done by Modernist urban planning,

- encourage architects to design buildings that fit in with and enhance traditional buildings by engaging in those traditions,

- and support the revival of the building arts without which we can neither preserve old buildings nor make new ones worthy of preservation.

TWO PRESERVATION PHILOSOPHIES

SLIDESHOW OF

MODERNIST ADDITIONS

“It sometimes feels as if cities like Paris and Venice have been coated with formaldehyde and turned into museums. The old formulas of ‘respecting context’ won’t work. We must create a new context and puncture past beauty with raw, powerful contemporary architecture—buildings that shock and amaze and bring out the romance of relics of Victorian and ancient times. It was once true that the palace, Palladian villas, and churches were architectural, while the other structures in a city were just buildings. But I think the art of architecture is ready to come out in every single structure we erect.”

SLIDESHOW OF

TRADITIONAL ADDITIONS

"...the answer to the problems of historic cities is neither sequestration nor 'penetration' but integration on the basis of knowledge and respect. Those of us who love beautiful historic cities and monuments must insist that economic authenticity and vitality for historic places require an architectural culture in which new and old are partners instead of antagonists... [We should] Change contemporary architecture from being the enemy of beauty to being the agent of its loving care. Train young architects in knowledge and respect for what is beautiful, sustainable and just in the historic environment and equip them with the skills needed to make more of it. Then we can put away the formaldehyde and instead nurture our cities with an economy and a building culture that will keep them alive, not as museums but as living cities once again available to all."

THE HISTORY OF PRESERVATION PHILOSOPHY

MODERNIST PRESERVATION

TRADITIONAL PRESERVATION

Modernist Preservation is often referred to as the Museum Approach to preservation because it is historicist in philosophy and curatorial in practice. It says that in order for a city to be a good city, it should have examples of architecture of all styles including the anti-traditional Modernist ones. It says that when a building or addition to a building is to be built it should be immediately identifiable as newer, even to the uninformed and even to the uninterested. Via the Venice Charter of 1964, and then the Secretary of Interior's Standards of 1977, this approach descends from the Modernist rhetoric of the 1920s and '30s, an approach that says that new traditional buildings in styles from the past are "inauthentic" and should not be allowed to be built, even if the owner wants it and the neighborhood is in favor. Examples of this approach are characterized by a call for architecture to be "of our time," and calls not for artistic harmony but for aesthetic contrast.

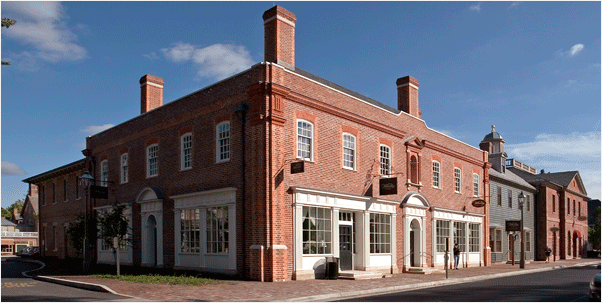

Pioneered in Charleston during the 1920s and crafted into a landmark Preservation Ordinance in 1931, the traditional approach to preservation is sometimes called the Area Approach because, rather than landmarking individual buildings only, it called for whole areas to be set aside as districts for traditional architecture both old and new, with new architecture to be built "in the historic styles." (Today we call these the traditional styles.) Modernism, at that time not yet named, was on the rise in Europe and in America (among architects and students), and in many cities citizens were not interested in purposefully-incongruous styles of architecture. Their cities were charming, their buildings beautiful, and they knew it. At the very time when Modernist architects were publishing their manifestos in Europe, Charleston and other American cities were in the midst of a renaissance. They had no reason to reject those principles that had built their lovely cities. Nor do we today.

The Museum Approach to preservation, combined with the fact that most new architecture is worse than what it replaces, results in preservationists with a death-grip on so-called "historic fabric," as Preservation has filled the vacuum of authority in matters of architecture left by the decline in public confidence in the architecture profession. Historic fabric and even whole buildings are often deemed "preservation worthy" without consideration for whether the material or building in question is beautiful, or useful, or otherwise valuable for the city. Even when a building is commonly recognized as ugly, or "non contributing," preservationists following the Museum Approach urge cities to save these buildings against their better judgement. An honest assessment reveals that these types of buildings are not only aesthetically incongruous, they are environmentally unsustainable. For preservationists to promote their ongoing maintenance in perpetuity is environmentally and socially irresponsible.

First Charleston in 1931, followed by New Orleans, Boston, Brooklyn Heights, etc, these Historic Districts might well have been called Historic-styles Districts, or rather Traditional Building Districts, for their purpose was clear: they were created not just to save old buildings but to restrict the intrusion of Modernism and to encourage the continued practice of the traditions of the place. In fact, for its first 35 years, the founding body tasked with enforcing the Area Approach had no power to restrict demolitions; its purpose was solely to ensure new construction in the District conformed to the Ordinance calling for "continued construction in the historic styles." A traditional city is a coherent one, one in which all of the buildings - even if stylistically eclectic - work together with the goal of presenting a harmonic civic hierarchy. Modernist philosophies reject civic typologies, thereby intentionally breaking the compositional harmony that generations of citizens have been working towards.

"The effort we are making now is against incongruity." (1958)

The Area Approach to preservation is NOT a call for the end of the construction of Modernist styles of buildings. It simply says that they are to be built outside certain small specified districts. By setting apart these Traditional Building Districts, the Area Approach provides variety and freedom of choice - between both areas of traditional building and areas of anti-traditional buildings.